Breaking the Ice in the Sunshine State

by Reuvain Borchardt – Hamodia.com

“I’m happy today to be joined by Officer Yehuda Topper from the North Miami Beach Police Department … Officer Topper took his talents to North Miami Beach from New York, where he was involved in law enforcement. And he’s the first Sabbath-observant Orthodox Jewish police officer … Welcome to Florida. Thank you for your service.”

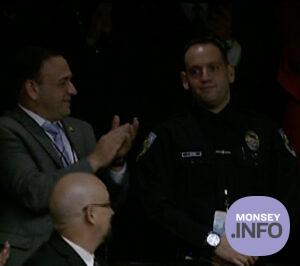

As Florida Gov. Ron Desantis recognized Yehuda Topper in his State of the State address Tuesday morning, the Sunshine State’s first Shomer Shabbos cop received an ovation as he stood in the gallery of the State Capitol in Tallahassee.

It appeared to be the culmination of what has been reported as a heartwarming story of tolerance and diversity, of a state with one of the largest Jewish populations in the nation finally getting its first Orthodox police officer, as well as the latest example of a demoralized New York Police Department officer leaving for a more cop-friendly department.

But the actual story is somewhat more complicated.

Yes, Yehuda Topper did leave the NYPD and join the North Miami Beach Police Department. Yes, he did seek a job in a state that he felt was tougher on crime than New York had become in recent years.

But Topper’s hiring in fact was fiercely opposed by the police union, who viewed his dispensation for Saturday and Jewish holidays as a violation of its seniority principles, in which rookie cops must work whenever and wherever they are told, while only more senior officers get to choose their schedules. It in fact took special intervention by police and city officials to get Topper his job. And, even after the positively reported news stories and the ovation in in Tallahassee, the union is planning to file grievances over Topper’s terms of employment — and the police and city officials say they are equally determined to stick up for what they view as a principled stance for religious liberties.

In exclusive interviews with Hamodia, some of the key figures tell the inside and ongoing story of a young man who says he wants nothing but to do his job quietly, but has become a symbol and the subject of a battle over unions, employment and religion in the Sunshine State.

—

It was 2020, and 32-year-old Yehuda Topper needed a change.

Topper had joined the NYPD two years earlier, seven years after becoming a paramedic for the City of New York.

He had grown up in New York, attended Yeshiva of South Shore in Long Island, and eventually moved to the Sheepshead Bay neighborhood of Brooklyn. But he and his wife, a Buffalo native, had agreed years earlier that they wanted to leave New York, but for one reason or another, that hadn’t worked out yet.

Yehuda worked to advance his career within city government, even as the Toppers had an eye to moving away from the Big Apple. He became a cop in 2018, intending to eventually gain enough service time to use his dual police and medic certification to join the NYPD’s Emergency Services Unit. In the meantime, he was assigned to the 77th Precinct in Crown Heights.

By 2020, his wife had received a good job offer with City College in Florida. And Yehuda had had enough of being a police officer in New York.

While he enjoyed working with his fellow cops and liked his commanding officers, “the politics and how things started becoming in regard to police officers in New York is really what” made him move, he says.

Even before the 2020 Black Lives Matter riots and subsequent police reforms resulted in thousands of NYPD officers leaving the force, Topper says a major factor for him was the bail reform passed by the state the previous year.

“They changed a lot of how policing has to be done, and now we’re operating with one hand behind our backs,” he says. “They changed bail laws. I’ve personally put people behind bars, and they’re out the next day — after committing violent felonies. I once fought with a perp on the ground over a loaded gun, and the guy’s out before I finished my arrest. This is somebody who had 60 or 70 arrests and is walking around with a loaded gun. That makes the entire city extremely dangerous.”

Given his wife’s job offer, and the Toppers having a number of relatives in Florida, Yehuda decided to look into becoming a police officer in that state. (This, he emphasizes, was long before Gov. Ron DeSantis, an opponent of vaccine mandates, recently offered a $5,000 bonus to police officers from other states – many of whom opposed their vaccine mandates – to relocate to Florida.)

Transferring police certification to another state can be a time-consuming process: while the officer would not have to attend the Florida police academy, he would have to take its law-enforcement exams, before deciding which of the myriad police departments in the state — county, city, sheriffs’ offices — he wanted to join.

But as Topper began to look into transferring to Florida, a major impediment arose.

As a rookie cop in whatever department he joined, he’d be starting at the bottom, with no say in his workdays and hours. He was expected to work nights, weekends, wherever and whenever he was told to. For an Orthodox Jew, who must refrain from work every week from Friday evening to Saturday night, as well as on Jewish holidays, this was a non-starter.

Florida police unions, like many public-sector unions around the nation, strictly enforce seniority rules, wherein longer-serving officers are given priority in choosing schedule. More-tenured officers waiting years for newer cops to join so they could move up the ladder, would not be happy that a rookie got to choose his schedule, taking off a day every weekend that older officers would love to have off and spend with their own families.

A rookie stating that he’d be unavailable on a particular day of the week is an automatic disqualification.

The argument that this scheduling exception was on a religious basis rather than personal preference didn’t sway the union; whatever the motivation behind the sought-for exemption, it was adamantly opposed.

It appeared that for Yehuda Topper, being a Florida cop would be a no-go.

Then, in early 2021, he was introduced to Rabbi Mark Rosenberg.

A transplanted Brooklynite, Rosenberg, director of Chesed Shel Emes in Florida, is a chaplain for several city, county and state police entities in that state.

Rosenberg was excited at the possibility of an Orthodox police officer, and understood the challenges that would have to be overcome. But he was determined to make it happen.

The chaplain encouraged Topper to take the exams, even without any guarantee that Topper wasn’t simply wasting his time. Topper passed easily.

Next, Rosenberg suggested that Topper choose the North Miami Beach Police Department: The 120-member force has its own SWAT team, where an in-house paramedic would be highly prized. With some 3,000 frum families, the city also boasted the largest year-round Orthodox population in the state — including Mark Rosenberg, who felt he could best use his connections there to try to help Topper get an exception not given to any rookie cop in recent memory.

If one needed a police chief from central casting, Richard Rand would be it.

North Miami Beach’s top cop speaks with intensity, spending at least half his interview with Hamodia emphasizing the importance of leadership. But it’s a friendly, enthusiastic intensity, bringing to mind an exceedingly polite drill sergeant.

He lights up upon seeing this reporter’s name on the Zoom window — “My name’s Reuvain, too,” he says, “Reuvain Dovid” — and appears delighted when he’s then asked about his religious affiliation.

He was born in North Miami Beach — growing up in a family he describes as “practicing Jews” — and he attended Hebrew school.

“I’ve never lost my contacts with the Jewish community,” he says, adding that “it honors me, especially recently, that I got to tie that into law enforcement. Because when law enforcement is going through a very difficult time, you see it New York, you see it here in North Miami Beach, and we’re under attack and people don’t like the police, I’m so proud to be able to see that the Jewish community always is the number-one community that comes forward and gives us coffee, gives us doughnuts, gives us cakes, gives us rugelach, gives us whatever it is, and just the heartfelt commitment that the community has to the police department is just tremendous. The Jewish community is a very strong community. I’m proud and honored to not only be an officer but to be of the Jewish faith.”

He also fondly recalls serving “matzah ball soup and blintzes” at his grandmother’s kosher restaurant in Bal Harbour (while conceding, when pressed by a snotty New York reporter, that Big Apple kosher delis are indeed superior).

When he heard about Topper’s desire to become a cop in North Miami Beach, the chief was all for it.

“Yehuda came very highly recommended to the police department as a possible candidate to become a police officer,” Rand says. “And me being Jewish, born and raised in the city of North Miami Beach, I really felt an immediate attraction to the idea, because we have the largest Orthodox Jewish population in Florida. Our Jewish community demands a lot of police protection — and I get it, with what’s going on in the world today, with Jews around the world being attacked. I thought that, while we represent all the other communities, do we really represent the Jewish community? Even though we have a Jewish chief, I have a couple of officers that are Jewish, but you take it to a different level when you’re talking about somebody that practices as an Orthodox Jew. And so I was very open to the idea. I actually loved it.”

Rand pushed the union representing his police officers to make this exception.

The issue, he believes — like most others — “really comes down to leadership.”

“Are people willing to follow you as a leader? Are people willing to believe what you’re saying as a leader? Are people willing to see your vision as a leader? And my folks here in this police department know what type of leader I am, know that I’m very transparent, know that the Jewish community is just as important to me as all of the communities are. And so when I went to the union, this is something that I delivered to them from my heart: I’m the chief of police. This is what I would like to see for our police department. This is what I would like to see for the city. This is what I would like to see for the Jewish community. This is what I would like to see for the state, and for the country. For us to be the first police department [in Florida] to hire an Orthodox Jewish person and be able to work it out within our rank and file so that we don’t have any issues.”

Rand and Deputy Chief of Police Ervens Ford fought for Topper. They fought hard.

But to their disappointment, the union’s response, according to Rand, amounted to, “We’re going to fight this. You’re going to have people that are very upset. There are a lot of people that want Friday night off that can’t get Friday night off.”

Rosenberg then knew Topper’s only hope was if the case were brought to the one person who could override the police union’s rules: City Manager Arthur Sorrey, the chief executive of North Miami Beach.

—

Arthur H. Sorey III admits that when he became city manager, “I didn’t know there was a Jewish community in North Miami Beach. I had no clue.”

It was only after assuming the position, he says, that “everybody’s telling me, ‘You better go over there to the other side of town.’” Sorey did go over to the “other side of town,” and quickly became what Rosenberg describes as “a friend to the community.”

It was in mid-November of 2021 that he first learned of the case of Yehuda Topper.

Sorey convened city officials including the police chief, city attorneys, the human resources department and the law-enforcement consultant, to discuss the case and find a path forward.

“The next morning,” he recalls, “we got Mr. Topper on the phone, went over everything, every possible scenario and what his expectations were, what do we need for him to be within his rights to work here.

“It’s hard for bureaucracy to get in the way when the final decision-maker sits at the table, so I just had a seat at the table and said, ‘Is that fine, is that fine’? and we got to the point where everything was fine. I just told him, ‘You get your medical, you come down, let me know and I’ll be there for you.’ And that was it. At that point, the ball was rolling too hard for anybody to stop it. And we got it done.”

All may have been “fine” for Sorey, Topper and the police brass, but all was not fine with the union, whose rules the city manager had used his power to override.

Sorey says he generally sympathizes with the union’s position on this issue.

“Somebody else might be a five-year officer on the seniority list, just waiting for that one new officer to come, so that he could get his Friday off — and now he’s going to get skipped over because the person can’t work Friday nights. So he has to stay there, and it holds up the process of somebody who might have been waiting for the process to play out for them.

“I understand that, but it doesn’t make sense this time, because now you’re discriminating on religion. If we were full of officers and we had no room for him, that’s one thing. But if I know we’re recruiting officers, that’s another whole thing. We recruited him. It’s after all the process. But then we get to the end and it’s like, ‘We can’t hire him because he can’t work on Saturday,’ — that doesn’t make any sense. And it wasn’t right.

“The unions didn’t evolve. You just talk about organization, and that’s just what the culture has been. And then see me come in, changing the culture on one person. But it was the right thing to do.”

—

In late December 2021, Yehuda Topper was officially hired as the first Sabbath-observing officer in the state.

“That’s when you know that the ice had been broken,” says Rosenberg. “The landscape of Florida has been changed by Mr. Sorey for everyone else. It means the world. It means that what you thought couldn’t happen, happened.”

Topper was sworn in on January 6, 2022.

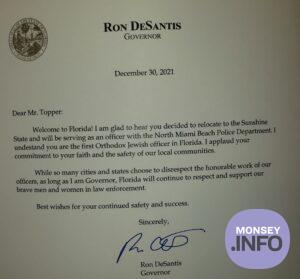

The news caused a stir in local and Jewish media. Gov. DeSantis wrote Topper a letter saying, “I applaud your commitment to your faith and the safety of our local communities.”

The police union still intends to file grievances on behalf of senior officers. But Sorey and Rand intend to argue that their decision was the proper one.

“Religion trumps contracts,” says Rand. “I am not willing to allow a contract to control the police department. We can’t allow things like that to get in the way of delivering the best services we can to the community. I’m anticipating some issues coming up in the future. But again, I’m very confident in my leadership, and I’m very confident in my staff that they will see how I see things and they will be willing to follow me through this.”

The North Miami Beach Police Association, local 6005 of the International Union of Police Associations, did not respond to Hamodia’s request for comment for this article.

—

DeSantis invited Topper to the State of the State address, where North Miami Beach’s newest police officer proudly wore his uniform and a yarmulke.

“It’s always good when somebody bites the bullet, and they take the heat for it; then everybody else can enjoy it now,” Sorey says smilingly, emphasizing that despite the governor’s basking in the news and his high-profile State of the State announcement, it was the city manager of North Miami Beach “who bit the bullet and said, ‘We’re going to do it.’”

But Sorey then concedes that the State of the State announcement is beneficial for his city. “It’s great. It puts us on the map.”

The North Miami Beach officials who advocated for Yehuda Topper are proud that the first Orthodox cop in Florida will be in their police department.

“I felt it was appropriate, and so did the city manager,” says Rosenberg, “because the whole idea of police reform is that these departments try to have the officers that match the community. How many Orthodox officers do we have in North Miami Beach? Now we have one,” noting that in addition to the symbolism, it is important in practical terms for the Orthodox community to have one of their own in office, who is familiar with their needs and considerations.

“One of the things that I’ve always believed in is legacy leadership: What legacy am I going to leave behind in this police department to make it a better police department than when I got here 25 years ago?” says Rand. “What an honor it is to be not only Jewish but to name the first Orthodox Jewish police officer here at North Miami Beach. When I retire, it’s really the footprint that we leave behind us. And this is really, to me, a footprint that the Jewish community will never forget, that North Miami Beach will never forget.”

And the officials hope that this is only the beginning of an expansion of religious liberties.

“Moving forward, I’ve taken the light and put the light now on the rest of Florida: Don’t discriminate against these officers that want to come down here,” says Sorey.

“This gives us encouragement, that everybody can be equally treated, regardless of your religion,” says Rosenberg, speculating that perhaps the next front in the battle will be in colleges, where professors still don’t easily give time off for Jewish holidays, noting that a relative of his once arrived home from a class at a local college 15 minutes before the Yom Kippur fast began.

—

And how does the rookie feel?

Basking in the glory? Gloating in the fame? Enjoying the spotlight?

None of the above.

Topper can’t quite be described as shy, but he is somewhat reserved, more out-of-town-than Brooklyn.

When Rand lets him sit at his desk and use his computer for the Hamodia Zoom interview, Topper shifts in the chief’s chair, visibly uncomfortable, saying, “It’s a very awkward position to be in.”

“It’s nice that everything turned out the way that it did,” he says, “but I’m not a publicity seeker. I’m usually the guy in the back of the room. I do what I’ve got to do and I go home. I’m just somebody who wanted to move here and work. That’s all I am.”

But Topper acknowledges that, like it or not, he may have become a trailblazer.

“The things that I was able to do for other people, it’s kind of eye-opening. I didn’t realize how big this was until this past week. So, if I could help somebody else out along the road, by doing something that nobody’s ever done before? Okay, I’m fine with that. But I’m not some big-time person or anything like that. I just was persistent. I did my due diligence,” emphasizing that his success is thanks to the efforts of his chief, deputy chief, police chaplain and city manager.

Topper feels he can be an asset to his fellow officers, rather than a burden, by volunteering to take shifts on Christian holidays and other times most officers wouldn’t want to work.

And he says that he has experienced “no resentment whatsoever” from his new colleagues.

“Everybody’s professional and courteous,” he says. “My interactions are, I’m the new guy, as much time as I had on the streets in New York City, in both EMS and the Police Department, here I’m at the bottom of the ladder. I know where I’m supposed to be. You respect the senior guys, you respect your rank and file and you know your place. I’m just another brand-new cop.”

But others in the city beg to differ.

“One of the founding principles of this nation was religious freedom — but that battle still has to be fought every day,” Rosenberg says. “People like Yehuda, and the officials who helped and encouraged him, from the police to local officials all the way up to the governor, just took another step toward ensuring that we are a nation that truly respects and cherishes religious liberties.”

My final query to my interviewees: “How do the mean streets of Brooklyn’s 77th Precinct compare to North Miami Beach? Who wants to answer that?”

It’s Rosenberg who jumps in.

“Is that even a question?”

—

rborchardt@hamodia.com